'It wasn't necessary to hit them with that awful thing!'

The Japanese were seeking to negotiate terms of surrender; Truman bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki anyway.

Introduction: Is it ever justifiable to target noncombatants?

This week marks the anniversary of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War II, a topic for which the recent release and success of the film Oppenheimer has reignited discussion.

The decision by President Harry Truman and his advisors to drop the atomic bombs has been highly controversial ever since it was made, yet there has been a range of justifications offered for the deed. The typical narrative taught in American history classes tells students that the bombings were the only alternative to invasion and occupation of the Japanese homeland, a scenario that would have resulted in millions of casualties on all sides. The Japanese were known for their fanatical devotion to their nation and their emperor, and were expected to fight to the last man, woman, and child. Thus, the civilian deaths at Hiroshima and Nagasaki were necessary to hasten the end of the war and prevent more deaths from an invasion.

This mainstream version of the bombings at least attempts to place a fig leaf of humanitarian concern (i.e. creating mass death in one instance to prevent much greater mass death in another instance) over a horrific act of wholesale slaughter, but one can encounter other justifications that are less concerned with appealing to any sense of morality.

There is the “total war” argument, which asserts that the very nature of a global conflict on the magnitude of World War II pushed the belligerent nations into circumstances where they had to largely overlook collateral damage, or even actively target non-combatants.

But the most pernicious apologiae for the bombings are those that justify it as an act of retribution. This is an attitude that is expected among jingoistic right-wingers who view the bombings as payback for the Japanese starting the war at Pearl Harbor, but a similar sentiment also exists among some left-wing “tankies” who believe that the fascist Japanese got what they deserved for their heinous atrocities against Koreans, Chinese, and others.

What both sides here share is an impoverished understanding of human nature, which in turn informs their distorted perception of masculine virtue. Both hold this Hobbesian view that man is essentially a beast, and this essence becomes especially evident in a state of war, which compels him to fully embrace his bestialism if he and his clan (or nation, race, etc.) are to survive. This view of man’s nature can lead one to valorize the bold, decisive leader who “does what needs to be done” in a time of war, who hardens his heart and is not restrained by “feminine” and “sentimentalist” feelings toward his enemies and their kinfolk.

Now, it is indeed true that “in times of war, the law falls silent,” as Cicero put it, and that such circumstances can and do bring out the savage beast even in the most civilized of men. Amidst the chaos of war, leaders are often forced to make tough, morally-ambiguous decisions, and some of those decisions result in civilian casualties—an unavoidable reality for all sides of a conflict.

It is also quite true that the Japanese imperial forces were responsible for a litany of abominable crimes against the peoples of the Far East that were comparable to those perpetrated by their Axis allies in Europe (a fact that, in the popular American discourse on World War II, does not receive even a fraction of the attention that the Holocaust does).

However, none of this can morally justify the decision to target civilians with atomic weapons (and the same goes for killing hundreds of thousands of Japanese and German civilians with incendiary bombs).

As kindergarteners, we get taught that “two wrongs don’t make a right.” Now, this can be dismissed as naive and moralistic, just a quaint little aphorism for children. Simple as it may be, it nevertheless does communicate an important fundamental moral truth in the same vein as Socrates' maxim that it is better to endure injustice than to commit it.

Man is not, in essence, a beast that must kill his conscience in order to survive extreme or desperate situations. Despite Cicero’s lamentation, our civilization has been able to evolve to the point where our modern civic and other institutions do formally recognize loftier moral concepts when dealing with questions of war and killing. While the notion of civilized warfare may be oxymoronic, international humanitarian law is designed to at least curb the excesses of armed conflict.

Indeed, there is still much hypocrisy and corruption that persists in the way that nations instigate and fight their wars today. However, this reality still does not invalidate the fact that achieving a consensus among the community of nations, in which they can agree to acknowledge the principle that the lives of noncombatants on all sides have inherent value and must be protected as far as possible, was a monumental accomplishment and an indicator of civilizational progress.

“His Majesty is anxious for a swift termination to the war.”

Hence, defending the bombings because “war is hell” or because the Japanese got their just desserts does not hold up. Now, to turn to the most "humanitarian" of the justifications—i.e. that the bombs were needed to force a Japanese surrender.

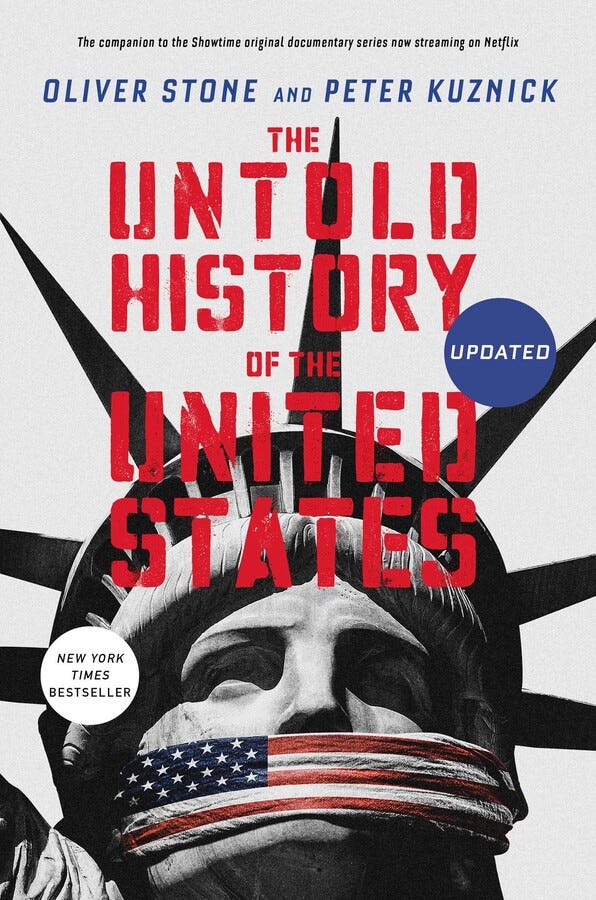

One of the most well-known refutations of this largely fictional textbook narrative comes from Hollywood filmmaker Oliver Stone. In 2012, Stone collaborated with American University historian Peter Kuznick for their project The Untold History of the United States, a 12-part documentary miniseries and its companion book, the subject of which is the ascent and reign of American global imperial hegemony.1

One episode of the miniseries (and a full chapter in the book) is dedicated entirely to the atomic bombs and their deployments against Japanese cities. According to Stone and Kuznick, it was becoming increasingly apparent that, by the end of 1944, Japan was facing defeat. The Allies had severely reduced her naval strength to only a fraction of what it had been at the beginning of the war, and her food and other supplies were dwindling. As early as February of the following year, Prince Konoe, a former prime minister and member of the Japanese nobility, wrote to Emperor Hirohito stating, “Japan's defeat is inevitable.”

By the spring of 1945, the Japanese foreign ministry was seeking out channels for mediating terms of surrender with the United States. They first tried this via the Vatican and then later via the Soviet Union. By this time, the European war had concluded, and the Japanese were dreading the eventuality that the Soviets, having defeated Germany, would soon be joining the other Allied Powers—China, the U.S., and the U.K.—in the Asia-Pacific. In July, Japan's Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo cabled his ambassador in Moscow, stating that Emperor Hirohito desired a “swift termination to the war.” Top U.S. officials—including Truman—were aware of this and other “Japanese maneuverings for peace.”

So if it is the case that Hirohito was looking to sue for peace, why were his overtures fruitless? Why did Truman resort to dropping the two atomic bombs—especially on civilian targets, slaughtering hundreds of thousands of innocents?

The answer to that starts with the shift in the American attitute towards area bombing.

“We must not get soft—war must be destructive and to a certain extent inhuman and ruthless.”

Aerial bombings of densely-populated civilian areas were a common practice in both the European and the Asia-Pacific wars. The United States, however, which did not enter the fighting until the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, initially opposed such tactics. President Franklin Roosevelt called them “sickening” and “inhuman barbarism”, and implored the belligerents to “under no circumstances undertake bombardment from the air of civilian populations in unfortified cities.” Army Air Corps General Henry "Hap" Arnold stated in 1940 that indiscriminate bombing was “contrary to our national policy of attacking only military objectives.”2

When U.S. forces did eventually enter the war, they concentrated only on precision bombing of key industries and transportation networks, undertaken in the daytime when visibility was high so as to avoid wanton death and destruction (though the technology at the time limited just how precise these “precision bombings” could be, thus resulting in collateral damage to civilians).

However, as the war went on, humanitarian considerations became less and less of a priority in U.S. bombardments. One of the most infamous of these is the U.S. Army Air Corps' participation in the British Royal Air Force's fire-bombing raid on the German city of Dresden in February of 1945, which devastated one of the most beautiful cultural meccas in Europe and massacred over 20,000 men, women, and children. General Arnold, in an about-face from his position in 1940, wrote in response to the controversy over Dresden: “We must not get soft—war must be destructive and to a certain extent inhuman and ruthless.”

As horrible as the bombing of Dresden was, the real precedent for the mass slaughter in Hiroshima and Nagasaki was the April 1945 bombing raid on Tokyo. Air attacks focused on the precision targeting of industrial and military targets on the Japanese main island of Honshu were approved by Roosevelt and the Joint Chiefs in 1943. Arnold placed Major General Curtis LeMay in charge of overseeing the operation, who ordered that U.S. bomber planes carry incendiary bombs—instead of merely explosive munitions—because they would be much more destructive in a city mostly consisting of buildings made of wood and paper. The most devastating of LeMay's raids took place in March 1945, where the use of incendiaries created firestorms that killed up to 200,000 Tokyoites—a greater death toll than either Hiroshima or Nagasaki.

Upon learning of LeMay's incendiary campaign, Henry Stimson, the Secretary of War for Roosevelt and eventually Truman, wrote that it was “appalling that there should be no protest in the United States over such wholesale slaughter”—although he did nothing in his capacity as War Secretary to put a stop to that slaughter.

LeMay later addressed the controversy in his 1965 memoir: “We knew we were going to kill a lot of women and kids… Had to be done… To worry about the morality of what we were doing—Nuts.”

Thus, the incendiary bombing raids had eroded the American conscience so that when the time came to use atomic weapons, there were fewer moral scruples.

“The main purpose of building this bomb is to subdue the Russians.”

What became known as the Manhattan Project to develop the very first nuclear weapons began shortly after the start of the European war in 1939, when a group of refugee scientists from Europe convinced Roosevelt that the Germans were developing an atomic bomb of awesome destructive power, and that the U.S. should therefore develop one first as a deterrent. Initially, Roosevelt approved only an advisory committee, but eventually gave the green light for the army to build a bomb in 1942.

In 1944, however, it had become clear that there was not going to be any German A-bomb, and by the end of that year, the European war was in its concluding phases. The question then turned to whether or not the bomb ought to be used against Japan.

In a memorandum drafted by U.K. Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Roosevelt signed off and agreed that an atomic weapon “might, perhaps, after mature consideration be used against the Japanese.” In private, Roosevelt would later elaborate on his interpretation of what “mature considerations” would entail: a non-military demonstration of the bomb’s power, potentially with a Japanese delegation present. If that demonstration failed to impress, the bomb could then be deployed against a target “of military value”. However, explicit warnings of the time and target of the attack were to be given, allowing for orderly civilian evacuation.3

One significant factor that likely influenced Roosevelt's plan to reserve the bomb only as a last resort was the eagerness many of his colleagues had to wield it as an instrument of world control, particularly as a means to intimidate the U.S.S.R. He told Henry Wallace, his former vice president, that he feared Churchill might want to utilize the superweapon against the Russians after the war. Top American officials involved in the project were also of a similar mind to Churchill: General Leslie Groves, the director of the Manhattan Project, was quoted by one of the project’s scientists admitting that “the main purpose… is to subdue the Russians.” Stimson wrote that the bomb could be used to bring Russia “into the fold of Christian civilization.” James Byrnes, the Roosevelt Administration’s head of the Office of War Mobilization who later became Truman’s Secretary of State—and effectively his handler—believed that the new superweapon could “make Russia more manageable in Europe.”

“If the Allies insist on unconditional surrender, Japan will fight to the bitter end.”

Roosevelt died before he could see the Pacific War through to the end, and the presidency that succeeded his took a much more cavalier attitude toward the atomic weapons. Shortly after the newly-inaugurated President Truman, who was previously unaware of the bomb’s existence, was briefed on the Manhattan Project, an Interim Committee was created to survey and make recommendations on its potential use. It was this committee that decided that the bomb should be used against Japan, but without most—if not all—of Roosevelt’s caveats. The only criterion in choosing a target was that it had some military value, meaning that there would be war production plants, port facilities, or military bases in the general vicinity.

Byrnes, Truman’s special representative on the committee, was adamant that the Japanese receive no advanced warning and had a report prepared for the interim committee recommending that the bomb be used against a “civilian-military target” so that it would have “maximum psychological effect.”

Meanwhile, the overtures by the Japanese to seek peace were disregarded. A major obstacle to negotiations was the Allies’ demand for unconditional surrender. Roosevelt first publicly called for the unconditional surrender of Germany, Japan, Itay and the rest of the Axis Powers at the Casablanca conference with Churchill in 1943. The phrase was formally adopted by Truman, Churchill, and Chinese Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek in the Potsdam Proclamation for Japanese Surrender near the end of July 1945, which also included the threat of “complete and utter destruction” if Tokyo failed to accept the unconditional surrender.

Japanese leaders feared that the term would mean the abolition of the imperial monarchy and the end of Japan as a nation-state. Togo in his telegram to the Moscow embassy stated that despite the emperor’s anxiousness to end the war, “[i]f the United States and Great Britain should insist on unconditional surrender, Japan would be forced to fight to the bitter end.”

There were attempts to urge Truman to clarify or modify America’s demand of unconditional surrender. Former ambassador to Tokyo Joseph Grew cautioned that surrender was highly unlikely without public assurances that the Japanese could retain the emperor. The Republican Congressional leadership called upon the president to further define what the U.S. position on “unconditional surrender” exactly meant, so that the war could be ended as soon as possible.

Days before the Potsdam Proclamation, Rear Admiral Ellis Zacharias, who was working the backchannels with Tokyo to lay out surrender terms, had a letter published in The Washington Post. The letter, which had the tacit approval of Navy Secretary James Forrestal but had not been cleared with any top personnel at the State Department or the White House, suggested that Japan could obtain surrender terms according to the Atlantic Charter (a joint statement Roosevelt and Churchill issued in 1941 stating that all people would have the right to self-determination in the post-war world).4

A few days later, Tokyo again cabled its ambassador in Moscow that the emperor had “no objection to a peace based on the Atlantic Charter” that allowed him and his subjects to “secure and maintain our nation's existence and honor,” but if the Allies were unwilling to entertain such terms, then the Japanese would “hold out until complete collapse.”

U.S. intelligence intercepted these cables, and top officials all the way up to Byrnes and Truman were informed of their contents, yet they dismissed the message. Later that same day, on July 25, Truman approved the order to deploy the bombs. It is worth noting that this final decision to bomb what were mostly civilian targets had been made before Tokyo responded to the Potsdam Proclamation. Ultimately, however, the emperor and his ministers did not accept the proclamation, citing that it was too vague on the eventual form of government for Japan. They also still held hopes that the Soviets could agree to broker negotiations for more specific peace terms.

“This is the greatest thing in history.”

However, what the Japanese leadership did not know is that the Americans had already committed to showing them exactly what “complete and utter destruction” meant, and the Soviets were already gearing up to invade Japanese-occupied Manchuria.

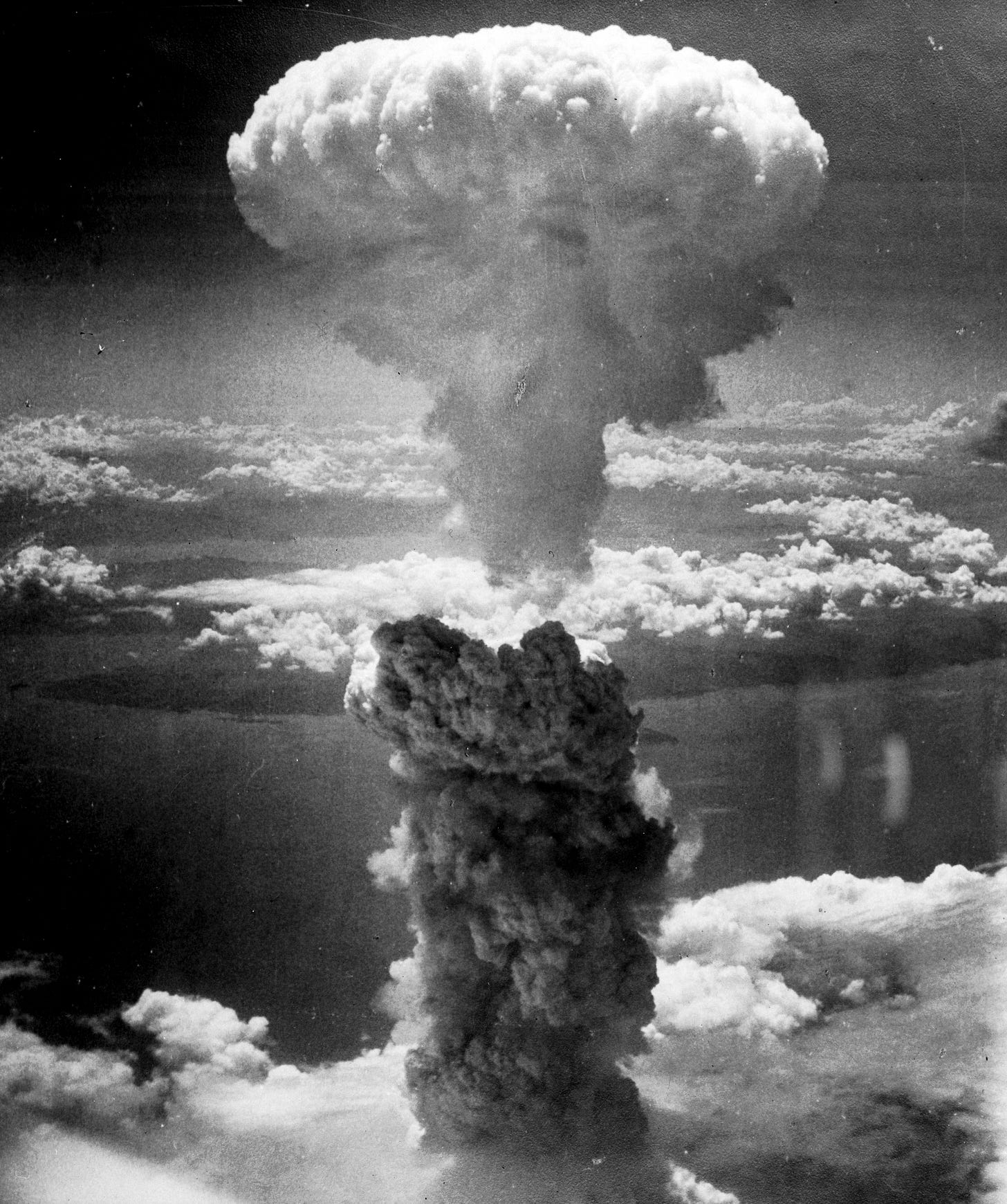

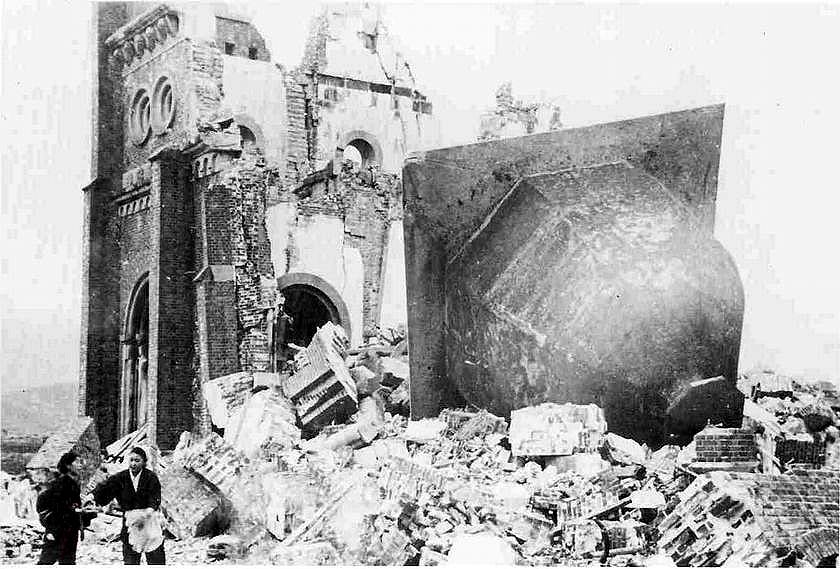

On the morning of August 6, the first bomb—“Little Boy”—was dropped on Hiroshima. The Japanese response was to immediately appeal again to Moscow to mediate peace talks. These hopes, however, were dashed when the Soviet Union declared war on Japan on August 8 and commenced the invasion of Manchuria. Mere hours later, on the morning of the 9th, another U.S. B-29 bomber dropped the second atomic bomb—“Fat Man”—on what is ironically the birthplace of Christianity in Japan: the city of Nagasaki.

Estimates of those killed by the combined bombings range from 150,000 to 220,000, the great majority of whom were noncombatants—including Korean slave laborers, Japanese-Americans (mostly children sent to live with relatives as their parents in the U.S. were being interned in camps), and American prisoners-of-war. An estimated 14,000 people died within 30 days from extreme radiation poisoning, and many survivors of the initial blasts would develop cancer years later.

When informed of the first bomb’s successful deployment, Truman responded, “This is the greatest thing in history,” to which Byrnes responded, “Fine! Fine!”

“Japan was ready to surrender and it wasn't necessary to hit them with that awful thing.”

In Untold History, Stone and Kuznick make the case that the Soviet Union’s entry into the Asia-Pacific War was, compared to the A-bombs, the greater deciding factor in forcing a swift surrender from Tokyo. The Japanese had already suffered the devastating incendiary attacks on their cities, and the full extent of the awesome, destructive power of atomic weapons was not yet entirely comprehended by Japanese leaders. In contrast, the Soviet Red Army’s invasion of Manchuria came as a much greater shock. Several Japanese military and civil officials attested to this, and the U.S. War Department concluded in 1946 that “it is almost a certainty that the Japanese would have capitulated upon the entry of Russia into the war.”

The emperor and his ministers concluded that surrendering to the U.S.A. would result in more favorable treatment compared to surrendering to the U.S.S.R., as the latter was more likely to demand the complete abolition of the imperial monarchy. Hirohito announced the acceptance of the Potsdam Proclamation, with the condition that it “does not compromise any demand which prejudices the prerogatives of His Majesty the Sovereign Ruler.” Washington accepted, responding that “the ultimate form of government shall… be established by the freely-formed will of the Japanese people.”

In the end, all the debate around “unconditional surrender” and the preservation of the monarchy needlessly prolonged the war. “[I]f the United States had agreed, as it later did anyway, to the retention of the institution of the Emperor,” General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Allied Commander in the Pacific, told journalist Norman Cousins, “[then t]he war might have ended weeks earlier.”

MacArthur was one of a number of America’s top military commanders who, as Stone and Kuznick state, “considered the bombs morally reprehensible, militarily unnecessary, or both.” Others included generals Eisenhower, Arnold, LeMay, and Spaatz; and admirals Nimitz, Leahy, Halsey, and King. In 1963, after serving as president, Dwight Eisenhower told a Newsweek interviewer that “the Japanese were ready to surrender and it wasn't necessary to hit them with that awful thing!”

“Threatening human extinction goes far beyond any war crime.”

Despite such objections coming directly from the men who did more to win the war than men like Truman or Byrnes did, the prevailing narrative concerning the bombings has become the one we are all too familiar with today: that they averted a protracted and bloody campaign to invade and occupy Japan, thus sparing countless lives.

That is not to say that the decision to drop the bombs is not still deemed today as one of the most controversial acts—if not the most controversial act—by Truman’s Presidency. Nevertheless, on the whole, Truman, in the majority of historical appraisals, is portrayed as being a resolute leader who did not shrink from doing the right thing when the time came.

Though surveys of academic historians typically rank him among the top 10 of all U.S. presidents, a more intellectually honest assessment of the historical record ought to lead one to a very opposite conclusion.

As Stone and Kuznick state:

“[Truman’s] decision to use the bomb against Japan was meant… as a ruthless and deeply unnecessary warning that the United States could be unrestrained by humanitarian considerations in using these same bombs against the Soviet Union… [And] on a larger moral scale, [he] knew he was beginning a process that could end life on the planet, …yet he forged ahead recklessly. Unnecessarily killing people is a war crime. Threatening human extinction goes far, far beyond that.”

Main Sources:

The Untold History of the United States (2012)

book by Oliver Stone and Peter Kuznick—Chapter 4: “The Tragedy of a Small Man”

documentary film directed by Oliver Stone—Episode 3: “The Bomb”

“Improvised Destruction: Arnold, LeMay, and the Firebombing of Japan” by William W. Ralph in War in History (October 2006)

“The Beast Men Behind the Dropping of the Atomic Bomb” by L. Wolfe in 21st Century Science and Technology (Spring 2005)

“How We Bungled the Japanese Surrender” by Ellis M. Zacharias in Look (June 6, 1950)